What Is Cultural Context in Setting

Cultural context in setting refers to the social, historical, and ideological environment in which a story takes place. It encompasses the beliefs, values, customs, and traditions that shape the characters’ worldviews and influence their actions. This context provides a rich backdrop against which the narrative unfolds, offering readers a deeper understanding of the characters’ motivations and the story’s themes.

Cultural context goes beyond mere physical descriptions of a place. It delves into the intangible aspects of a society that define its identity and govern its members’ behavior. For example, in a story set in Victorian England, the cultural context would include the rigid class structure, strict moral codes, and gender roles that characterized that era.

The cultural context of a setting can be conveyed through various elements:

Social structures: The hierarchies, power dynamics, and relationships within a society.

Historical background: The events and circumstances that have shaped the society’s current state.

Traditions and customs: The rituals, celebrations, and practices that are unique to the culture.

Beliefs and values: The moral, religious, and philosophical principles that guide the society.

Language and communication: The verbal and non-verbal ways in which people interact.

Economic systems: The ways in which goods and services are produced, distributed, and consumed.

Artistic expressions: The literature, music, art, and other creative outputs that reflect the culture.

Understanding cultural context is essential for both writers and readers. For writers, it provides a framework for creating authentic and believable worlds. For readers, it offers insights into unfamiliar societies and enhances their appreciation of the story’s nuances.

Consider the following example of how cultural context can be woven into a setting description:

“As Mei Lin stepped onto the bustling streets of 1920s Shanghai, she was acutely aware of the clash between tradition and modernity. The scent of incense from nearby temples mingled with the exhaust fumes of newly imported automobiles. Men in Western suits hurried past women in traditional qipao dresses, while street vendors called out in a mix of Shanghainese and English. The city pulsed with the energy of change, yet ancestral shrines still occupied places of honor in many homes, a testament to the enduring power of ancient beliefs in this rapidly modernizing world.”

This description not only paints a vivid picture of the physical setting but also captures the cultural tensions and transitions of the time, providing a rich context for the story to unfold.

How does cultural context differ from physical setting?

While cultural context and physical setting are both integral components of a story’s backdrop, they differ significantly in their nature and function. Understanding these differences is crucial for writers to create a fully realized world for their narratives.

Physical Setting

The physical setting refers to the tangible, observable aspects of the environment where the story takes place. It includes:

- Geographical location (e.g., a city, country, or planet)

- Time period (e.g., historical era or future time)

- Climate and weather conditions

- Natural features (e.g., mountains, rivers, forests)

- Man-made structures (e.g., buildings, roads, monuments)

- Sensory details (e.g., sights, sounds, smells)

Physical settings provide the concrete stage on which the story unfolds. They can be described in detail, allowing readers to visualize the environment clearly.

Cultural Context

Cultural context, on the other hand, encompasses the intangible aspects of the setting that shape the characters’ worldviews and behaviors. It includes:

- Social norms and expectations

- Historical background and collective memory

- Religious and philosophical beliefs

- Political systems and power structures

- Economic conditions and class divisions

- Artistic and literary traditions

- Technological advancements and their impact on society

Cultural context is often more subtle and complex than physical setting. It requires deeper exploration and understanding to convey effectively.

To illustrate the difference, consider the following comparison:

| Aspect | Physical Setting | Cultural Context |

|---|---|---|

| Nature | Tangible, observable | Intangible, conceptual |

| Description | Can be directly described | Often implied or shown through character interactions |

| Time frame | Can be static | Dynamic, evolving over time |

| Impact on characters | Influences actions and movements | Shapes thoughts, beliefs, and motivations |

| Reader engagement | Helps visualization | Enhances understanding of character behavior |

| Research required | Geographical and historical facts | Sociological, anthropological, and historical studies |

While physical setting and cultural context are distinct, they often intertwine to create a rich, immersive story world. For example, in Gabriel García Márquez’s “One Hundred Years of Solitude,” the fictional town of Macondo serves as both a physical setting and a microcosm of Latin American culture. The town’s isolation and the magical events that occur there reflect the broader themes of colonialism, progress, and the cyclical nature of history that are central to the novel’s cultural context.

Writers must skillfully balance the depiction of physical setting and cultural context to create a fully realized world. While the physical setting can be described more directly, cultural context often emerges through character interactions, dialogue, and the unfolding of events. By weaving these elements together, authors can create stories that not only transport readers to different places but also immerse them in the complex social and cultural landscapes that shape their characters’ lives.

Why is cultural context important in storytelling?

Cultural context plays a vital role in storytelling, enriching narratives and providing depth to characters and plot. Its importance extends beyond mere background information, significantly impacting the reader’s engagement and understanding of the story.

Authenticity and Believability

Cultural context lends authenticity to a story, making it more believable and relatable. When characters act in ways that align with their cultural background, readers find them more credible. This authenticity allows readers to suspend disbelief and immerse themselves fully in the narrative world.

For instance, in Khaled Hosseini’s “The Kite Runner,” the cultural context of Afghanistan, including its traditions, social hierarchies, and historical events, provides a rich backdrop that makes the characters’ actions and motivations believable within their specific setting.

Character Development

Cultural context shapes characters’ worldviews, values, and behaviors. It influences their decision-making processes, relationships, and personal conflicts. By understanding a character’s cultural background, readers can better comprehend their motivations and internal struggles.

In Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s “Half of a Yellow Sun,” the characters’ actions and choices are deeply influenced by their Igbo culture and the political turmoil in Nigeria during the Biafran War. This cultural context adds layers of complexity to their personalities and relationships.

Plot Progression

The cultural context often drives the plot forward by creating conflicts, obstacles, or opportunities for the characters. Societal expectations, historical events, or cultural traditions can serve as catalysts for the story’s events.

For example, in Jane Austen’s “Pride and Prejudice,” the cultural norms of 19th-century England regarding marriage and social class are central to the plot, driving many of the characters’ actions and the story’s conflicts.

Theme Exploration

Cultural context allows writers to explore universal themes through specific cultural lenses. It provides a framework for examining issues such as identity, belonging, tradition versus modernity, or cultural clash.

Jhumpa Lahiri’s “The Namesake” uses the cultural context of Indian immigrants in America to explore themes of identity, assimilation, and the generational gap, giving these universal concepts a unique and poignant treatment.

Reader Engagement and Education

A well-crafted cultural context can engage readers by introducing them to unfamiliar worlds and perspectives. It can broaden their understanding of different cultures and historical periods, fostering empathy and cultural awareness.

Yaa Gyasi’s “Homegoing” spans centuries and continents, offering readers insights into Ghanaian history and culture, as well as the African American experience, through its rich cultural context.

Symbolic and Metaphorical Depth

Cultural context can provide a wealth of symbols and metaphors that add depth to the narrative. Cultural artifacts, traditions, or beliefs can carry significant meaning within the story.

In Gabriel García Márquez’s “Love in the Time of Cholera,” the cultural context of 19th-century Colombia, with its emphasis on honor and tradition, provides rich symbolism that enhances the story’s themes of love and time.

Language and Communication

The cultural context influences the language used in the story, including dialects, idioms, and communication styles. This linguistic aspect can add authenticity and flavor to the narrative.

Zora Neale Hurston’s “Their Eyes Were Watching God” uses African American Vernacular English to authentically represent the characters’ voices and cultural background.

Cultural context in storytelling is not just about adding color or exotic flavor to a narrative. It is a fundamental element that shapes characters, drives plots, explores themes, and engages readers on multiple levels. By skillfully incorporating cultural context, writers can create stories that are not only entertaining but also insightful, authentic, and capable of broadening readers’ perspectives on the diverse world we inhabit.

What are the key elements of cultural context?

Cultural context in storytelling is composed of several interconnected elements that collectively create a rich tapestry of social, historical, and ideological factors. Understanding these key elements allows writers to craft authentic and immersive story worlds. Here are the essential components of cultural context:

Social Structure and Hierarchy

This element encompasses the organization of society, including class systems, caste structures, and social mobility. It defines how individuals relate to one another and their positions within the community.

In “To Kill a Mockingbird” by Harper Lee, the social hierarchy of 1930s Alabama, with its racial segregation and class distinctions, is central to the story’s conflicts and character interactions.

Historical Background

The historical context includes past events, traditions, and collective memories that shape the present reality of the story’s setting. It provides the foundation for understanding the characters’ world and their place in it.

“Things Fall Apart” by Chinua Achebe is deeply rooted in the historical context of pre-colonial and colonial Nigeria, exploring the impact of European colonization on traditional Igbo society.

Religious and Philosophical Beliefs

This element encompasses the spiritual and ideological frameworks that guide individuals and societies. It includes organized religions, philosophical traditions, and folk beliefs.

In Yann Martel’s “Life of Pi,” the protagonist’s exploration of multiple religions forms a significant part of the cultural context, influencing his worldview and actions throughout the story.

Political Systems and Power Dynamics

The political landscape, including forms of government, distribution of power, and ideological conflicts, plays a crucial role in shaping the cultural context.

George Orwell’s “1984” is set in a dystopian society where the political system of totalitarian control defines every aspect of the characters’ lives and thoughts.

Economic Systems

The economic structure, including modes of production, distribution of wealth, and economic philosophies, significantly influences the cultural context.

John Steinbeck’s “The Grapes of Wrath” is deeply rooted in the economic context of the Great Depression, exploring its impact on rural American families.

Gender Roles and Relations

Societal expectations and norms regarding gender influence character behavior, relationships, and opportunities within the story world.

Margaret Atwood’s “The Handmaid’s Tale” presents a dystopian society where extreme gender roles and reproductive rights form a central part of the cultural context.

Family Structure and Kinship

The organization of families, marriage customs, and kinship systems are crucial elements of cultural context that influence character relationships and social obligations.

In Amy Tan’s “The Joy Luck Club,” the Chinese-American family structures and intergenerational relationships are central to the cultural context of the story.

Education and Knowledge Systems

The ways in which knowledge is valued, transmitted, and acquired within a society form an important part of the cultural context.

In Tara Westover’s memoir “Educated,” the contrast between her isolated, anti-establishment upbringing and formal education systems forms a key part of the cultural context.

Artistic and Creative Expressions

Literature, music, visual arts, and other forms of creative expression reflect and shape the cultural context of a society.

In Tracy Chevalier’s “Girl with a Pearl Earring,” the artistic world of 17th-century Dutch painting provides a rich cultural context for the story.

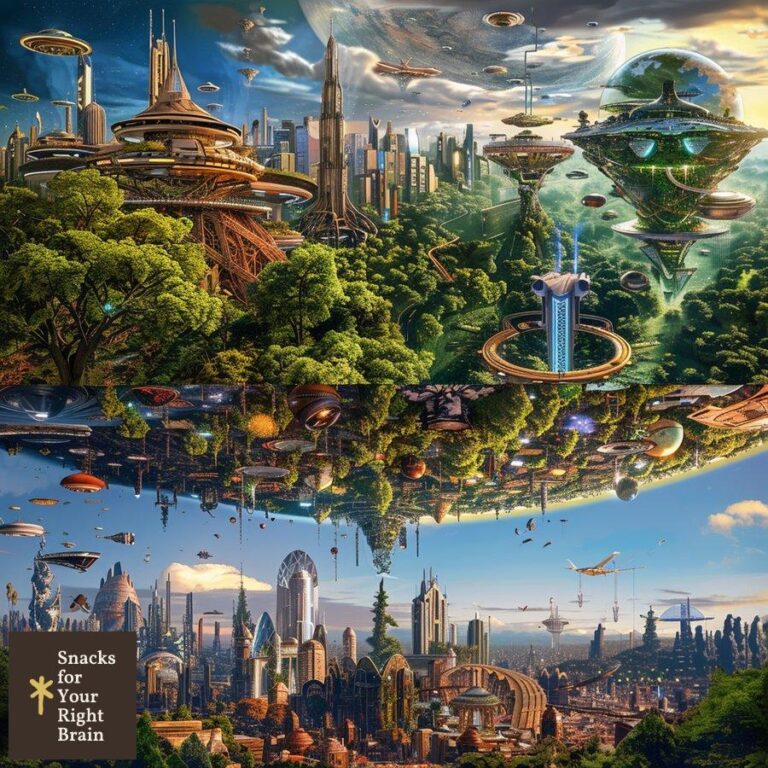

Technological Advancement

The level of technological development and its impact on society is an increasingly important element of cultural context, especially in contemporary or futuristic settings.

Ernest Cline’s “Ready Player One” is set in a future where virtual reality technology has dramatically altered social interactions and economic systems, forming a crucial part of the cultural context.

Language and Communication

The languages spoken, dialects used, and communication norms (including non-verbal communication) are integral to cultural context.

Anthony Burgess’s “A Clockwork Orange” uses a fictional slang called Nadsat, which forms a significant part of the cultural context of its dystopian setting.

These elements of cultural context are not isolated; they interact and influence each other, creating a complex web of cultural factors. Writers must consider how these elements work together to create a cohesive and authentic cultural backdrop for their stories. By skillfully incorporating these elements, authors can create rich, immersive worlds that not only entertain readers but also provide insights into diverse human experiences and societies.

How does cultural context influence character development?

Cultural context plays a pivotal role in shaping characters, influencing their personalities, motivations, conflicts, and growth throughout a story. It provides the framework within which characters are formed and developed, affecting every aspect of their existence within the narrative. Understanding this influence is crucial for writers to create authentic, multi-dimensional characters that resonate with readers.

Shaping Core Values and Beliefs

A character’s fundamental values and beliefs are often deeply rooted in their cultural context. These core principles guide their decision-making processes and moral judgments throughout the story.

In Khaled Hosseini’s “The Kite Runner,” the protagonist Amir’s actions and internal conflicts are heavily influenced by the Afghan concepts of honor, loyalty, and redemption. His journey of personal growth is intrinsically tied to these cultural values.

Defining Social Roles and Expectations

Cultural context determines the roles characters are expected to fulfill within their society. These expectations can create internal and external conflicts as characters either conform to or rebel against these prescribed roles.

In Jane Austen’s “Pride and Prejudice,” Elizabeth Bennet’s character development is closely tied to her navigation of the societal expectations for women in 19th-century England. Her struggle against these norms forms a central part of her character arc.

Influencing Interpersonal Relationships

The cultural context shapes how characters interact with one another, including family dynamics, friendships, and romantic relationships. It defines acceptable behaviors, communication styles, and the nature of various social bonds.

Amy Tan’s “The Joy Luck Club” explores how the cultural context of Chinese immigrants in America influences mother-daughter relationships across generations, shaping the characters’ interactions and understanding of one another.

Creating Internal Conflicts

Characters often experience internal struggles when their personal desires or beliefs clash with the expectations or norms of their cultural context. This conflict can be a powerful driver of character development.

In Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s “Americanah,” the protagonist Ifemelu grapples with issues of identity and belonging as she navigates between Nigerian and American cultures, leading to significant personal growth and self-discovery.

Determining Opportunities and Limitations

The cultural context can define the opportunities available to characters or the limitations they face, based on factors such as social class, gender, or ethnicity. Characters may strive to overcome these limitations, shaping their goals and aspirations.

In Frank McCourt’s memoir “Angela’s Ashes,” the poverty and social constraints of 1930s Ireland significantly impact the author’s childhood experiences and aspirations, shaping his character development throughout the narrative.

Influencing Worldview and Perspective

A character’s cultural context shapes their understanding of the world, influencing how they interpret events, judge others, and perceive themselves. This worldview can evolve as characters encounter different cultural contexts.

In Jhumpa Lahiri’s “The Namesake,” the protagonist Gogol’s perspective on his identity and cultural heritage evolves as he navigates between his Indian roots and American upbringing.

Providing Motivation for Growth and Change

Cultural context can provide the impetus for character growth, either through characters striving to fulfill cultural ideals or rebelling against cultural constraints.

In Lisa See’s “Snow Flower and the Secret Fan,” the characters’ development is deeply tied to their navigation of the strict cultural norms for women in 19th-century China, driving their actions and personal growth throughout the story.

Shaping Language and Communication Styles

The way characters express themselves, including their use of language, idioms, and non-verbal communication, is heavily influenced by their cultural context. This aspect of character development can provide insight into their background and personality.

In Mark Twain’s “Adventures of Huckleberry Finn,” the distinctive dialects and speech patterns of the characters reflect their cultural and social backgrounds, contributing significantly to their characterization.

Influencing Reactions to Change and Conflict

How characters respond to challenges, conflicts, or changes in their environment is often shaped by their cultural context. Their coping mechanisms, problem-solving approaches, and emotional responses are culturally influenced.

In Chinua Achebe’s “Things Fall Apart,” Okonkwo’s reactions to the encroachment of colonial powers on his traditional Igbo society are deeply rooted in his cultural context, driving his character’s tragic arc.

Defining Personal and Societal Goals

The aspirations and objectives of characters are often shaped by what their culture values and considers successful or praiseworthy. This influences their life choices and the direction of their character development.

In F. Scott Fitzgerald’s “The Great Gatsby,” Jay Gatsby’s pursuit of wealth and status is driven by the American Dream, a cultural ideal that shapes his character’s motivations and actions throughout the novel.

By understanding and skillfully incorporating these aspects of cultural influence on character development, writers can create rich, authentic characters that not only feel real to readers but also provide insights into the complexities of human nature and the profound impact of cultural context on individual lives.

In what ways does cultural context impact plot progression?

Cultural context plays a significant role in shaping the plot of a story, influencing its progression, conflicts, and resolutions. It provides the framework within which events unfold and characters interact, often driving the narrative forward in unique and compelling ways.

Creating Conflict

Cultural norms, expectations, and taboos can be a rich source of conflict in storytelling. When characters’ desires or actions clash with societal expectations, it creates tension that propels the plot forward.

In Edith Wharton’s “The Age of Innocence,” the rigid social norms of 19th-century New York high society create the central conflict as the protagonist struggles between his duty to his fiancée and his passion for a socially unacceptable woman.

Defining Stakes

The cultural context often determines what is at stake for the characters, influencing the weight and significance of their choices and actions. What might be a minor issue in one culture could be life-altering in another.

In Khaled Hosseini’s “A Thousand Splendid Suns,” the cultural context of Afghanistan under Taliban rule raises the stakes for the female protagonists, as their very survival depends on navigating oppressive societal norms.

Shaping Character Motivations

Cultural values and beliefs often drive characters’ motivations, influencing their goals and the actions they take to achieve them. This, in turn, shapes the direction of the plot.

In Amy Tan’s “The Joy Luck Club,” the desires and actions of the Chinese-American daughters are influenced by both their Chinese heritage and American upbringing, driving various subplots within the overall narrative.

Providing Plot Catalysts

Cultural events, rituals, or traditions can serve as catalysts for plot progression, providing opportunities for character interaction, conflict, or revelation.

In Gabriel García Márquez’s “Chronicle of a Death Foretold,” the cultural expectations surrounding honor and virginity set in motion the events that lead to the protagonist’s death, forming the central plot of the novella.

Influencing Plot Resolution

The way conflicts are resolved in a story often reflects the cultural context. Societal norms and values can dictate acceptable solutions or outcomes to the story’s central problems.

In Jane Austen’s “Sense and Sensibility,” the resolution of the romantic plots is heavily influenced by the social and economic expectations of 19th-century England, shaping how the characters’ relationships evolve and conclude.

Determining Pacing

Cultural context can influence the pacing of a story by dictating the speed at which events unfold or decisions are made. Some cultures may value quick action, while others prioritize deliberation and consensus.

In Kazuo Ishiguro’s “The Remains of the Day,” the reserved nature of English society and the protagonist’s adherence to the code of butler service result in a slow, introspective pacing that reflects the cultural context.

Creating Obstacles

Cultural factors can create obstacles that characters must overcome, adding complexity to the plot. These obstacles might be societal prejudices, legal restrictions, or cultural misunderstandings.

In Jhumpa Lahiri’s “The Namesake,” the cultural differences between Indian and American societies create various obstacles for the protagonist as he navigates his identity, relationships, and career.

Providing Historical Backdrop

The historical aspects of cultural context can provide a rich backdrop against which the plot unfolds, often intertwining personal stories with larger historical events.

In Michael Ondaatje’s “The English Patient,” the cultural and historical context of World War II and its aftermath shapes the plot, influencing the characters’ actions and relationships.

Influencing Character Arcs

As characters navigate their cultural context, their growth and development shape the plot’s progression. Character arcs often involve embracing, rejecting, or reconciling aspects of their cultural background.

In Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s “Americanah,” the protagonist’s journey between Nigerian and American cultures drives her personal growth and the plot’s development.

Determining Consequences

The consequences of characters’ actions are often determined by their cultural context. What might be rewarded in one culture could be punished in another, significantly impacting the plot’s direction.

In Nathaniel Hawthorne’s “The Scarlet Letter,” the severe consequences of adultery in Puritan New England drive the entire plot, shaping the characters’ lives and relationships.

By skillfully weaving cultural context into plot progression, writers can create stories that are not only engaging but also provide insight into the complex interplay between individuals and their societal framework. This approach adds depth and authenticity to the narrative, making it more resonant and meaningful for readers.

How can writers research and analyze cultural context?

Researching and analyzing cultural context is a crucial step for writers aiming to create authentic and immersive stories. This process requires a combination of academic research, personal exploration, and critical analysis. Here are several effective approaches writers can use:

Academic Research

Writers can delve into scholarly works to gain a comprehensive understanding of their chosen cultural context.

- Historical texts: Study primary and secondary historical sources to understand the time period and societal structures.

- Anthropological studies: Explore ethnographies and cultural analyses for insights into social norms, beliefs, and practices.

- Sociological research: Examine studies on social structures, institutions, and group dynamics within the culture.

Literature and Media

Engaging with creative works from or about the culture can provide valuable insights.

- Literature: Read novels, short stories, and poetry by authors from the culture you’re researching.

- Films and documentaries: Watch visual media that depicts the culture, both fictional and non-fictional.

- Music and art: Explore the artistic expressions of the culture for emotional and aesthetic understanding.

Personal Interviews

Conducting interviews with individuals from the culture can offer firsthand perspectives and personal anecdotes.

- Cultural insiders: Speak with people who have lived experiences within the culture.

- Experts and scholars: Consult academics specializing in the culture or time period.

- Community leaders: Engage with individuals who hold positions of influence within the culture.

Immersive Experiences

When possible, immersing oneself in the culture can provide invaluable insights.

- Travel: Visit locations relevant to your story to experience the environment firsthand.

- Cultural events: Attend festivals, ceremonies, or other cultural gatherings.

- Language learning: Study the language of the culture to understand linguistic nuances and thought patterns.

Online Resources

The internet offers a wealth of information and connections for cultural research.

- Cultural organization websites: Explore sites dedicated to preserving and sharing cultural heritage.

- Online forums and social media: Engage in discussions with members of the culture.

- Virtual tours and exhibitions: Take advantage of digital resources offered by museums and cultural institutions.

Government and NGO Reports

Official documents can provide valuable data and insights into various aspects of a culture.

- Census data: Analyze demographic information for a deeper understanding of population dynamics.

- Economic reports: Study economic structures and trends within the culture.

- Human rights reports: Examine documents on social issues and cultural practices.

Analyzing Cultural Context

Once the research is gathered, writers need to analyze this information effectively:

Identify Key Elements

- Social structures: Understand hierarchies, power dynamics, and social mobility.

- Belief systems: Analyze religious, philosophical, and ideological frameworks.

- Traditions and customs: Examine rituals, celebrations, and daily practices.

- Historical influences: Consider how past events shape current cultural norms.

Look for Patterns and Contradictions

- Cultural values: Identify recurring themes in behavior, art, and social structures.

- Generational differences: Analyze how cultural norms evolve over time.

- Subcultures: Explore variations within the broader cultural context.

Consider Multiple Perspectives

- Insider vs. outsider views: Compare how the culture is perceived internally and externally.

- Marginalized voices: Seek out perspectives from different social groups within the culture.

- Historical context: Understand how cultural perceptions have changed over time.

Analyze Cultural Products

- Art and literature: Examine how creative works reflect and shape cultural values.

- Media representation: Analyze how the culture is portrayed in various media forms.

- Language use: Study idioms, slang, and communication styles for cultural insights.

Ethical Considerations

Writers must approach cultural research and representation ethically:

- Avoid stereotyping: Recognize the diversity within cultures and avoid oversimplification.

- Respect sensitivity: Be aware of cultural taboos and approach sensitive topics with care.

- Acknowledge limitations: Recognize and be transparent about the limits of your understanding as an outsider.

- Seek feedback: Consult with cultural insiders to verify accuracy and authenticity.

By employing these research methods and analytical approaches, writers can develop a nuanced and respectful understanding of cultural contexts. This deep knowledge allows for the creation of rich, authentic story worlds that resonate with readers and provide meaningful insights into diverse human experiences.

What role do social norms and customs play in cultural context?

Social norms and customs are fundamental components of cultural context, playing a crucial role in shaping the behaviors, expectations, and interactions within a society. They provide the unwritten rules that guide social behavior and form the foundation of cultural identity. Understanding the role of social norms and customs is essential for writers to create authentic and immersive story worlds.

Defining Acceptable Behavior

Social norms establish the boundaries of what is considered appropriate or inappropriate within a culture.

- Etiquette: They dictate manners and polite behavior in various social situations.

- Taboos: Norms also define what is forbidden or socially unacceptable.

In Kazuo Ishiguro’s “The Remains of the Day,” the protagonist’s adherence to the strict norms of English butler service defines his behavior and worldview.

Shaping Social Interactions

Customs and norms guide how individuals interact with one another in different contexts.

- Greetings: They determine appropriate ways to acknowledge others.

- Personal space: Norms dictate acceptable physical proximity in social situations.

- Conflict resolution: They influence how disagreements are addressed and resolved.

In Amy Tan’s “The Joy Luck Club,” the interactions between Chinese immigrant mothers and their American-born daughters are shaped by differing social norms from Chinese and American cultures.

Establishing Hierarchies and Power Dynamics

Social norms often reflect and reinforce power structures within a society.

- Age and seniority: Many cultures have specific norms regarding respect for elders.

- Gender roles: Norms can dictate different expectations and behaviors for men and women.

- Social class: Customs may vary between different socioeconomic groups.

Gabriel García Márquez’s “One Hundred Years of Solitude” vividly portrays how social norms and customs reinforce the power dynamics in the fictional town of Macondo.

Marking Life Stages and Transitions

Customs often accompany significant life events, marking transitions and milestones.

- Coming of age rituals: Many cultures have specific customs for entering adulthood.

- Marriage ceremonies: Wedding customs vary widely across cultures.

- Funeral rites: Practices surrounding death and mourning are deeply cultural.

In Chinua Achebe’s “Things Fall Apart,” Igbo customs surrounding various life stages play a crucial role in the narrative and character development.

Preserving Cultural Identity

Social norms and customs serve as a means of maintaining and transmitting cultural identity.

- Traditional practices: They keep historical and cultural practices alive.

- Language use: Linguistic norms preserve unique aspects of cultural communication.

- Dress codes: Clothing customs can be a visible marker of cultural identity.

Jhumpa Lahiri’s “The Namesake” explores how Indian immigrants in America navigate between preserving their cultural customs and adapting to new social norms.

Creating Social Cohesion

Shared norms and customs create a sense of belonging and unity within a culture.

- Collective rituals: Practices that bring communities together.

- Shared values: Norms often reflect and reinforce common cultural values.

- Social expectations: They create a framework for mutual understanding and cooperation.

In Jane Austen’s novels, the shared social norms of Regency England create a cohesive social world that characters must navigate.

Influencing Decision Making

Social norms often guide individual and collective decision-making processes.

- Moral judgments: They influence what is considered right or wrong.

- Career choices: Norms can affect what professions are valued or stigmatized.

- Lifestyle decisions: They impact choices in areas like marriage, family size, or living arrangements.

In Khaled Hosseini’s “A Thousand Splendid Suns,” the characters’ decisions are heavily influenced by the social norms of Afghan society.

Adapting to Change

While norms and customs can be deeply ingrained, they also evolve over time.

- Generational shifts: Younger generations may challenge or modify existing norms.

- Cultural contact: Interaction with other cultures can lead to changes in customs.

- Technological impact: New technologies can alter social norms and customs.

Margaret Atwood’s “The Handmaid’s Tale” depicts a society where drastic changes in social norms have been forcibly implemented, exploring the impact on individuals and society.

Creating Conflict and Tension

In storytelling, social norms and customs can be a rich source of conflict and tension.

- Internal conflict: Characters may struggle with adhering to or rejecting social norms.

- Interpersonal conflict: Differing adherence to norms can create tension between characters.

- Societal conflict: Challenging established norms can lead to broader social tensions.

In Edith Wharton’s “The Age of Innocence,” the conflict between personal desire and adherence to social norms drives the entire narrative.

By understanding and effectively incorporating social norms and customs into their narratives, writers can create rich, authentic cultural contexts that not only provide a backdrop for their stories but also drive character development, conflict, and thematic exploration. This attention to the nuances of social norms and customs allows for the creation of immersive story worlds that resonate with readers and offer insights into the complexities of human societies.

How does language reflect cultural context in literature?

Language is a powerful tool in literature that not only serves as a medium of communication but also as a reflection of cultural context. It carries within it the history, values, worldviews, and social structures of a culture. Writers use language strategically to create authentic characters, establish setting, and convey cultural nuances. Here’s how language reflects cultural context in literature:

Vocabulary and Lexicon

The words available in a language often reflect what is important or prevalent in a culture.

- Specialized terminology: Cultures may have extensive vocabulary for things central to their way of life.

- Loanwords: The presence of words borrowed from other languages can indicate cultural contact or influence.

- Idioms and proverbs: These often encapsulate cultural wisdom and values.

In George Orwell’s “1984,” the invented language “Newspeak” reflects the totalitarian culture’s attempt to control thought through language.

Grammatical Structures

The way a language is structured can reflect cultural thought patterns and social hierarchies.

- Honorifics: Some languages have complex systems for showing respect or social status.

- Gender in language: The presence or absence of grammatical gender can reflect cultural views on gender.

- Time concepts: How tenses are used can indicate cultural perceptions of time.

In Arundhati Roy’s “The God of Small Things,” the use of Malayalam words and syntax in English reflects the cultural hybridity of post-colonial India.

Dialects and Sociolects

Variations in language use can indicate social class, education level, or regional background.

- Regional dialects: These can place characters geographically and culturally.

- Social dialects: Different social groups within a culture may use language differently.

- Code-switching: Characters may switch between languages or dialects in different contexts.

Mark Twain’s use of different dialects in “Adventures of Huckleberry Finn” reflects the social and racial divisions of 19th-century America.

Taboo and Euphemism

What can and cannot be said directly often reflects cultural values and sensitivities.

- Profanity: The nature of what is considered profane varies across cultures.

- Euphemisms: How sensitive topics are discussed indirectly can be culturally specific.

- Silence: What is left unsaid can be as culturally significantas what is spoken.

In Amy Tan’s “The Joy Luck Club,” the indirect communication style of the Chinese-born characters contrasts with the more direct style of their American-born children, reflecting cultural differences in expression.

Metaphors and Symbolism

The figurative language used in literature often draws from culturally specific references and symbols.

- Nature metaphors: These often reflect the physical environment and its cultural significance.

- Cultural symbols: Objects or concepts may carry specific meanings within a culture.

- Religious allusions: References to religious texts or concepts can be deeply embedded in language use.

Salman Rushdie’s “Midnight’s Children” is rich with metaphors and symbols drawn from Indian culture and mythology, reflecting the cultural context of post-independence India.

Narrative Style

The way stories are told can reflect cultural values and traditions.

- Oral storytelling traditions: Some cultures have specific narrative structures passed down orally.

- Circular vs. linear narratives: Different cultures may have different concepts of how stories should unfold.

- Collective vs. individual focus: Some cultures emphasize communal narratives over individual ones.

Gabriel García Márquez’s use of magical realism in “One Hundred Years of Solitude” reflects Latin American storytelling traditions and worldviews.

Forms of Address

How characters address each other can indicate social relationships and cultural norms.

- Formal vs. informal: The choice between formal and informal address can reflect social distance or intimacy.

- Titles and honorifics: The use of titles can indicate social status or profession.

- Kinship terms: How family members are addressed can reflect family structures and cultural values.

In Jane Austen’s novels, the formal modes of address reflect the rigid social structure of Regency England.

Multilingualism and Language Mixing

The presence of multiple languages or language mixing in literature can reflect cultural diversity or conflict.

- Code-switching: Characters may switch between languages, reflecting their multicultural identities.

- Untranslated words: Leaving certain words in their original language can emphasize their cultural significance.

- Pidgins and creoles: The use of these languages can reflect histories of cultural contact and colonialism.

Junot Díaz’s “The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao” uses a mix of English and Spanish, reflecting the Dominican-American experience.

Humor and Wordplay

What is considered funny and how humor is expressed can be deeply cultural.

- Puns and wordplay: These often rely on cultural and linguistic knowledge.

- Satire: The targets and methods of satire can reflect cultural values and critiques.

- Irony: The use and understanding of irony can vary across cultures.

The humor in Terry Pratchett’s Discworld series often relies on British cultural references and wordplay.

Naming Conventions

Character names can carry significant cultural meaning.

- Historical or mythological references: Names may allude to cultural heroes or legends.

- Descriptive names: Some cultures use names that describe personal qualities or circumstances of birth.

- Generational naming patterns: How names are passed down can reflect family structures and values.

In Toni Morrison’s “Song of Solomon,” character names like Milkman and Pilate carry symbolic weight tied to African American cultural history.

By skillfully incorporating these linguistic elements, writers can create a rich and authentic cultural context in their literature. Language becomes not just a means of communication, but a window into the cultural world of the characters, allowing readers to immerse themselves in different cultural perspectives and experiences. This deep integration of language and cultural context enhances the depth and authenticity of the narrative, making the story more engaging and meaningful for readers.

What is the significance of religious and philosophical beliefs in cultural settings?

Religious and philosophical beliefs form a cornerstone of cultural settings, profoundly influencing individual and collective worldviews, moral frameworks, and social structures. These belief systems permeate various aspects of life, shaping characters’ motivations, conflicts, and the overall narrative landscape. Understanding their significance is crucial for writers aiming to create authentic and nuanced cultural contexts in their stories.

Shaping Worldviews and Values

Religious and philosophical beliefs provide the lens through which characters interpret the world and their place in it.

- Moral frameworks: These beliefs often define concepts of right and wrong, good and evil.

- Purpose and meaning: They offer explanations for life’s purpose and the nature of existence.

- Cosmology: Beliefs about the universe’s origin and structure influence characters’ perspectives.

In Yann Martel’s “Life of Pi,” the protagonist’s exploration of multiple religions shapes his understanding of the world and his survival story.

Influencing Social Structures

Belief systems often underpin social hierarchies and institutions.

- Family structures: Religious beliefs can dictate family roles and relationships.

- Gender roles: Many religions and philosophies have specific views on gender and sexuality.

- Social hierarchies: Beliefs can justify or challenge existing power structures.

Khaled Hosseini’s “A Thousand Splendid Suns” depicts how religious interpretations shape social structures and gender roles in Afghan society.

Driving Rituals and Traditions

Religious and philosophical beliefs manifest in tangible practices that mark important life events and cycles.

- Rites of passage: Beliefs often dictate ceremonies for birth, coming of age, marriage, and death.

- Festivals and holidays: These celebrations reflect and reinforce cultural beliefs.

- Daily rituals: Beliefs can influence everyday practices, from prayer to dietary habits.

In Jhumpa Lahiri’s “The Namesake,” Hindu rituals and traditions play a significant role in the characters’ lives, even as they navigate a new cultural context in America.

Creating Conflict and Tension

Differences in beliefs, or conflicts between belief and action, can drive narrative tension.

- Internal conflict: Characters may struggle with doubts or contradictions within their belief systems.

- Interpersonal conflict: Differing beliefs can create tension between characters.

- Societal conflict: Clashes between different belief systems can lead to larger social tensions.

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s “Purple Hibiscus” explores the tension between traditional Catholicism and Igbo beliefs, as well as the conflict between religious devotion and domestic abuse.

Providing Comfort and Coping Mechanisms

Beliefs often offer solace and strategies for dealing with life’s challenges.

- Explanations for suffering: Religions and philosophies often provide frameworks for understanding hardship.

- Rituals of healing: Beliefs can offer practices for coping with grief, illness, or misfortune.

- Community support: Shared beliefs can foster a sense of belonging and mutual aid.

In Alice Walker’s “The Color Purple,” spirituality provides the protagonist with strength and a sense of self-worth in the face of oppression.

Influencing Art and Expression

Religious and philosophical beliefs often inspire and shape artistic expression.

- Symbolism: Belief systems provide a rich source of symbols and metaphors.

- Artistic themes: Religious stories and philosophical concepts often appear in literature and other art forms.

- Aesthetic styles: Beliefs can influence visual arts, music, and architecture.

Salman Rushdie’s “The Satanic Verses” incorporates Islamic mythology and philosophy into its narrative structure and themes.

Shaping Language and Communication

Beliefs influence the way people speak and the concepts they can express.

- Religious vocabulary: Specific terms and phrases related to beliefs become part of everyday language.

- Metaphysical concepts: Beliefs provide language for discussing abstract or spiritual ideas.

- Taboos and euphemisms: Beliefs often dictate what can be said directly and what must be alluded to indirectly.

In James Joyce’s “A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man,” Catholic terminology and concepts permeate the protagonist’s thoughts and the narrative style.

Influencing Education and Knowledge Systems

Beliefs play a role in determining what knowledge is valued and how it is transmitted.

- Educational institutions: Many schools and universities have religious or philosophical foundations.

- Accepted truths: Beliefs can influence what is considered factual or important to learn.

- Intellectual traditions: Philosophical schools of thought shape academic disciplines and approaches.

Tara Westover’s memoir “Educated” explores how her family’s religious beliefs shaped her unconventional education and worldview.

Providing Ethical Frameworks for Science and Technology

Beliefs often guide societal responses to scientific and technological advancements.

- Bioethics: Religious and philosophical beliefs influence debates on issues like genetic engineering or end-of-life care.

- Environmental ethics: Beliefs about humanity’s relationship with nature affect approaches to environmental issues.

- Technological ethics: Philosophical frameworks help navigate the moral implications of new technologies.

In Margaret Atwood’s “Oryx and Crake,” religious and philosophical beliefs intersect with scientific advancement, shaping the dystopian world and characters’ actions.

Influencing Political Systems and Ideologies

Beliefs often underpin political philosophies and systems of governance.

- Theocracies: Some societies base their political systems directly on religious beliefs.

- Secular philosophies: Even in non-religious contexts, philosophical beliefs shape political ideologies.

- Civil religion: Patriotic beliefs and rituals can function similarly to religious systems.

George Orwell’s “1984” depicts a totalitarian system that functions like a secular religion, with its own rituals, beliefs, and thought control.

By understanding and incorporating the multifaceted influence of religious and philosophical beliefs, writers can create rich, authentic cultural settings that resonate with readers. These belief systems provide depth to characters, drive conflicts, and offer insights into the complexities of human societies. When skillfully woven into the narrative fabric, they enhance the story’s thematic exploration and provide a deeper understanding of the cultural context in which the characters live and act.

How have famous authors effectively used cultural context in their works?

Famous authors have masterfully employed cultural context to enrich their narratives, create authentic characters, and explore complex themes. Their effective use of cultural elements not only enhances the story’s realism but also provides readers with insights into diverse societies and human experiences. Here are some notable examples of how renowned authors have utilized cultural context in their works:

Chinua Achebe – “Things Fall Apart”

Achebe’s seminal novel is a prime example of effective use of cultural context.

- Igbo culture: The author meticulously depicts Igbo customs, beliefs, and social structures.

- Colonialism: The novel explores the clash between traditional Igbo culture and European colonialism.

- Language: Achebe incorporates Igbo proverbs and storytelling techniques into the narrative.

Achebe’s work not only tells a compelling story but also serves as a cultural document, preserving and explaining Igbo traditions to a global audience.

Gabriel García Márquez – “One Hundred Years of Solitude”

Márquez’s masterpiece is deeply rooted in Latin American culture and history.

- Magical realism: The author blends fantastical elements with reality, reflecting Latin American storytelling traditions.

- Colombian history: The novel allegorically represents key events in Colombian and Latin American history.

- Family dynamics: Márquez explores complex family relationships typical of Latin American culture.

The author’s use of cultural context creates a rich, immersive world that has captivated readers worldwide.

Toni Morrison – “Beloved”

Morrison’s novel is steeped in African American cultural history.

- Slavery’s legacy: The author explores the deep-seated trauma of slavery in African American culture.

- Folklore: Morrison incorporates elements of African American folk traditions and supernatural beliefs.

- Oral tradition: The narrative style reflects the importance of storytelling in African American culture.

Morrison’s use of cultural context adds depth to her characters and provides a powerful exploration of African American history and identity.

Salman Rushdie – “Midnight’s Children”

Rushdie’s novel is a cultural tapestry of post-independence India.

- Historical events: The author weaves India’s political history into the narrative.

- Religious diversity: The novel reflects India’s complex religious landscape.

- Linguistic richness: Rushdie incorporates multiple languages and dialects, reflecting India’s linguistic diversity.

Through his use of cultural context, Rushdie creates a narrative that is both personally intimate and nationally epic.

Jane Austen – “Pride and Prejudice”

Austen’s novel is a masterful portrayal of early 19th-century English society.

- Social norms: The author meticulously depicts the manners and expectations of Regency England.

- Class structure: Austen explores the rigid class hierarchy of her time.

- Gender roles: The novel examines the limited options available to women in that era.

Austen’s acute observation of cultural details creates a vivid picture of her society while exploring universal themes of love and prejudice.

Khaled Hosseini – “The Kite Runner”

Hosseini’s novel provides a deep dive into Afghan culture and history.

- Historical context: The author traces Afghanistan’s tumultuous history from the 1970s to the early 2000s.

- Cultural traditions: Hosseini depicts Afghan customs, particularly those surrounding kite flying.

- Social hierarchies: The novel explores ethnic and class divisions in Afghan society.

Hosseini’s use of cultural context not only enriches the story but also provides readers with insights into a culture often misunderstood in the West.

Jhumpa Lahiri – “The Namesake”

Lahiri’s novel explores the Indian-American immigrant experience.

- Cultural identity: The author examines the challenges of balancing two cultures.

- Generational differences: Lahiri contrasts the experiences of first-generation immigrants with their American-born children.

- Naming traditions: The novel explores the significance of names in Indian culture.

Lahiri’s nuanced portrayal of cultural context illuminates the complexities of the immigrant experience.

Haruki Murakami – “Kafka on the Shore”

Murakami’s novel blends Japanese culture with Western influences.

- Shinto mythology: The author incorporates elements of traditional Japanese beliefs.

- Western philosophy: Murakami weaves in references to Western literature and thought.

- Contemporary Japan: The novel reflects aspects of modern Japanese society.

Murakami’s unique blend of cultural elements creates a dreamlike narrative that resonates with readers across cultures.

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie – “Half of a Yellow Sun”

Adichie’s novel is deeply rooted in Nigerian history and culture.

- Biafran War: The author explores this pivotal event in Nigerian history.

- Igbo culture: Adichie depicts Igbo customs and beliefs.

- Colonialism’s legacy: The novel examines the lasting impact of British colonialism on Nigerian society.

Adichie’s use of cultural context provides a nuanced portrayal of Nigerian history and identity.

Isabel Allende – “The House of the Spirits”

Allende’s novel is steeped in Chilean history and Latin American magical realism.

- Political history: The author allegorically represents Chile’s political upheavals.

- Class dynamics: Allende explores the relationships between different social classes in Chilean society.

- Spirituality: The novel incorporates elements of spiritualism common in Latin American culture.

Allende’s rich cultural tapestry creates a multi-generational saga that is both personally intimate and politically resonant.

These authors demonstrate that effective use of cultural context goes beyond mere description. They integrate cultural elements seamlessly into their narratives, using them to develop characters, drive plots, and explore themes. By doing so, they create works that are not only entertaining but also culturally illuminating, offering readers windows into diverse worlds and experiences. Their success lies in their ability to make the specific universal, using particular cultural contexts to explore fundamental human experiences and emotions that resonate across cultural boundaries.

What techniques can writers use to create authentic cultural contexts?

Creating authentic cultural contexts in literature requires a combination of thorough research, empathy, and skillful writing techniques. Here are several effective techniques that writers can employ to craft genuine and immersive cultural settings:

Immersive Research

Thorough research is the foundation of creating authentic cultural contexts.

- Primary sources: Study historical documents, diaries, and firsthand accounts.

- Field research: If possible, visit the location or immerse yourself in the culture.

- Interviews: Speak with people from the culture you’re writing about.

Example: For “The Kite Runner,” Khaled Hosseini drew from his own experiences growing up in Afghanistan and conducted extensive research on the country’s recent history.

Sensory Details

Use vivid sensory descriptions to bring the cultural setting to life.

- Sights: Describe architecture, clothing, and landscapes unique to the culture.

- Sounds: Include local music, languages, and ambient noises.

- Smells and tastes: Describe local cuisine and environmental scents.

Example: In “Like Water for Chocolate,” Laura Esquivel uses rich sensory details of Mexican cuisine to evoke the cultural setting and emotions of her characters.

Language and Dialogue

Incorporate authentic language use to reflect the cultural context.

- Dialects and accents: Use phonetic spelling or rhythm to conveyunique speech patterns.

- Idioms and proverbs: Include culturally specific sayings and expressions.

- Code-switching: If appropriate, show characters switching between languages.

Example: Junot Díaz’s “The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao” seamlessly blends English and Spanish, reflecting Dominican-American culture.

Cultural Practices and Rituals

Integrate cultural customs and traditions into the narrative.

- Daily routines: Show how characters engage in culturally specific daily activities.

- Celebrations: Depict festivals, holidays, and important cultural events.

- Rites of passage: Include ceremonies marking significant life stages.

Example: In “Memoirs of a Geisha,” Arthur Golden meticulously describes the rituals and practices of geisha culture in Japan.

Social Structures and Hierarchies

Reflect the social organization of the culture in character interactions.

- Class dynamics: Show how social class affects characters’ lives and relationships.

- Gender roles: Depict culturally specific expectations for men and women.

- Age and seniority: Reflect cultural attitudes towards age and experience.

Example: Jane Austen’s novels expertly portray the social hierarchies and gender expectations of Regency England.

Belief Systems

Incorporate religious, philosophical, and superstitious beliefs into the story.

- Religious practices: Show how characters engage with their faith.

- Folklore and mythology: Include cultural stories and legends.

- Superstitions: Depict beliefs about luck, fate, and the supernatural.

Example: Salman Rushdie’s “Midnight’s Children” weaves Hindu mythology and Indian folklore into its narrative structure.

Historical Context

Ground the story in the historical realities of the culture.

- Political events: Show how major historical events impact characters’ lives.

- Social movements: Depict cultural shifts and societal changes.

- Technological advancements: Reflect the level of technology appropriate to the time and place.

Example: Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s “Half of a Yellow Sun” is set against the backdrop of the Biafran War, a crucial event in Nigerian history.

Cultural Values and Worldviews

Reflect the core values and perspectives of the culture in character motivations and conflicts.

- Moral frameworks: Show how cultural values influence characters’ decisions.

- Concepts of success: Depict culturally specific ideas of achievement and failure.

- Attitudes towards nature: Reflect cultural relationships with the environment.

Example: In “Things Fall Apart,” Chinua Achebe portrays Igbo values and worldviews through the protagonist’s actions and beliefs.

Material Culture

Include authentic details about objects and artifacts specific to the culture.

- Clothing: Describe traditional and contemporary dress.

- Architecture: Depict buildings and living spaces unique to the culture.

- Art and crafts: Include descriptions of cultural artistic expressions.

Example: Amy Tan’s “The Joy Luck Club” includes detailed descriptions of Chinese artifacts and their significance to the characters.

Avoid Stereotyping

Present a nuanced view of the culture, avoiding oversimplification or exoticization.

- Show diversity: Depict variations within the culture.

- Avoid caricatures: Present complex, multi-dimensional characters.

- Challenge assumptions: Subvert common stereotypes about the culture.

Example: Jhumpa Lahiri’s “The Namesake” presents a nuanced view of Indian-American culture, avoiding stereotypical portrayals.

Consult Cultural Insiders

Seek feedback from members of the culture you’re writing about.

- Sensitivity readers: Have people from the culture review your work.

- Expert consultations: Speak with scholars or cultural experts.

- Community engagement: Engage with cultural communities for insights and feedback.

Example: For “Memoirs of a Geisha,” Arthur Golden consulted extensively with a former geisha to ensure cultural accuracy.

Use of Narrative Perspective

Choose a narrative voice that authentically represents the cultural perspective.

- First-person cultural insider: Use a narrator deeply embedded in the culture.

- Third-person cultural lens: Employ a narrative voice that reflects cultural attitudes and perceptions.

- Multiple perspectives: Use various viewpoints to show different aspects of the culture.

Example: Arundhati Roy’s “The God of Small Things” uses a narrative voice deeply rooted in Kerala culture to tell its story.

By employing these techniques, writers can create rich, authentic cultural contexts that enhance their narratives and provide readers with meaningful insights into diverse cultures. The key is to approach the task with respect, thorough research, and a commitment to authenticity. This not only makes for more engaging storytelling but also contributes to greater cross-cultural understanding and appreciation.

How does cultural context affect reader interpretation and engagement?

Cultural context plays a crucial role in shaping how readers interpret and engage with literature. It influences the way readers understand characters, plot elements, themes, and the overall message of a work. The interplay between the cultural context of the story and the reader’s own cultural background can significantly impact the reading experience. Here’s an exploration of how cultural context affects reader interpretation and engagement:

Frame of Reference

Cultural context provides readers with a frame of reference for understanding the story.

- Familiar contexts: Readers may find it easier to relate to stories set in familiar cultural contexts.

- Unfamiliar contexts: Stories set in unfamiliar cultures may require more effort to understand but can also be more enlightening.

Example: A reader from a collectivist culture might interpret the actions of characters in an individualistic society differently than a reader from an individualistic culture.

Character Motivation and Behavior

Cultural context influences how readers interpret characters’ actions and motivations.

- Cultural norms: Readers assess character behavior based on their understanding of what’s normal or acceptable in the story’s cultural context.

- Value systems: The cultural values depicted in the story may align or conflict with the reader’s own values, affecting their judgment of characters.

Example: In Khaled Hosseini’s “The Kite Runner,” Western readers might initially struggle to understand the protagonist’s actions, which are deeply rooted in Afghan concepts of honor and redemption.

Emotional Resonance

The cultural context can affect the emotional impact of the story on readers.

- Cultural significance: Events or symbols that hold deep meaning in one culture may not have the same emotional resonance for readers from different backgrounds.

- Shared experiences: Readers may feel a stronger connection to stories that reflect experiences common in their own culture.

Example: The significance of foot-binding in Lisa See’s “Snow Flower and the Secret Fan” might evoke different emotional responses from Chinese readers familiar with the historical practice compared to readers from other cultures.

Thematic Interpretation

Cultural context influences how readers interpret the themes and messages of a story.

- Cultural lens: Readers often interpret themes through the lens of their own cultural values and beliefs.

- Universal vs. culturally specific themes: Some themes may be seen as universal, while others might be interpreted as specific to the culture depicted.

Example: The theme of individual freedom in George Orwell’s “1984” might be interpreted differently by readers from societies with varying degrees of personal liberty.

Language and Communication

The use of language in the story, influenced by cultural context, affects reader engagement.

- Linguistic familiarity: Readers may find it easier to engage with text that uses familiar linguistic patterns or expressions.

- Untranslated words or concepts: The inclusion of culturally specific terms can either enhance authenticity or create distance, depending on the reader’s background.

Example: The use of Spanglish in Junot Díaz’s works might increase engagement for bilingual readers while potentially creating challenges for monolingual readers.

Historical and Social Understanding

The reader’s knowledge of the historical and social context depicted in the story affects their interpretation.

- Historical events: Familiarity with historical events referenced in the story can deepen understanding and engagement.

- Social structures: Understanding the social norms of the depicted era or culture enhances comprehension of character relationships and conflicts.

Example: A reader’s interpretation of Toni Morrison’s “Beloved” is greatly enhanced by an understanding of the history of slavery in the United States.

Cultural Assumptions and Stereotypes

Readers’ preexisting cultural assumptions can influence their interpretation of the story.

- Confirmation or challenge of stereotypes: Stories may either reinforce or challenge readers’ preconceptions about a culture.

- Cultural misunderstandings: Lack of familiarity with a culture may lead to misinterpretations of characters’ actions or motivations.

Example: Western readers might misinterpret the actions of characters in Yasunari Kawabata’s “Snow Country” if they’re unfamiliar with Japanese cultural norms and aesthetics.

Empathy and Perspective-Taking

Cultural context in literature can foster empathy and encourage readers to adopt new perspectives.

- Cross-cultural understanding: Exposure to different cultural contexts can broaden readers’ worldviews.

- Identification with characters: Readers may find themselves identifying with characters from different cultural backgrounds, fostering empathy.

Example: Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s “Americanah” offers readers insights into the experiences of Nigerian immigrants in the United States, potentially fostering greater empathy and understanding.

Intertextuality and Cultural References

The cultural context influences how readers interpret allusions and references within the text.

- Cultural knowledge: Readers with knowledge of the cultural references will have a richer reading experience.

- Missed connections: Readers unfamiliar with cultural references may miss layers of meaning in the text.

Example: Readers familiar with Greek mythology will have a deeper appreciation of the allusions in Madeline Miller’s “Circe.”

Reader Expectations and Genre Conventions

Cultural context shapes reader expectations about story structure and genre conventions.

- Narrative structures: Different cultures may have varying expectations about how stories should be told.

- Genre expectations: Cultural context influences what readers expect from different literary genres.

Example: Western readers might find the non-linear narrative structure of some non-Western literature challenging if they’re accustomed to more linear storytelling.

Critical Analysis and Interpretation

The cultural context of both the reader and the text influences critical analysis and interpretation.

- Cultural bias: Readers’ own cultural backgrounds may influence their critical approach to the text.

- Multicultural perspectives: Exposure to different cultural contexts in literature can lead to more nuanced critical analysis.

Example: Postcolonial readings of classic Western literature, such as Jean Rhys’s “Wide Sargasso Sea” as a response to Charlotte Brontë’s “Jane Eyre,” demonstrate how cultural context affects critical interpretation.

Understanding the impact of cultural context on reader interpretation and engagement is crucial for both writers and readers. For writers, it highlights the importance of creating authentic, well-researched cultural contexts and considering diverse readerships. For readers, awareness of cultural context enhances the reading experience, encouraging more nuanced interpretations and fostering cross-cultural understanding. Ultimately, the interplay between the cultural context of the story and the reader’s own background can lead to richer, more meaningful engagements with literature, broadening perspectives and deepening appreciation for diverse human experiences.

What challenges do readers face when encountering unfamiliar cultural contexts?

Readers often encounter various challenges when engaging with literature set in unfamiliar cultural contexts. These challenges can affect comprehension, interpretation, and overall enjoyment of the text. Understanding these difficulties is crucial for both readers seeking to broaden their literary horizons and writers aiming to make their work accessible to diverse audiences. Here are the main challenges readers face and strategies to overcome them:

Linguistic Barriers

Unfamiliar languages, dialects, or linguistic patterns can pose significant challenges.

- Untranslated words: Texts may include words or phrases in languages unknown to the reader.

- Idiomatic expressions: Culturally specific idioms may be difficult to understand.

- Syntax and grammar: Unfamiliar linguistic structures can make comprehension challenging.

Strategy: Use context clues to deduce meanings, consult glossaries (if provided), or research unfamiliar terms. Some readers find it helpful to keep a personal glossary as they read.

Example: The mix of English and Hindi in Salman Rushdie’s “Midnight’s Children” can be challenging for readers unfamiliar with Indian languages.

Conceptual Gaps

Readers may struggle with concepts or ideas that are taken for granted within the depicted culture but are unfamiliar to outsiders.

- Social norms: Behaviors that are normal in one culture may seem strange or inexplicable in another.

- Belief systems: Religious or philosophical concepts may be difficult to grasp without background knowledge.

- Historical context: Lack of familiarity with historical events can hinder understanding of characters’ motivations and plot developments.

Strategy: Research the cultural and historical background of the text before or while reading. Look for explanatory notes or companion guides that provide context.

Example: Understanding the concept of “face” in Chinese culture is crucial for fully appreciating Amy Tan’s “The Joy Luck Club.”

Misinterpretation of Cultural Cues

Readers may misunderstand or misinterpret cultural cues, leading to incorrect assumptions about characters or situations.

- Non-verbal communication: Gestures or body language may have different meanings across cultures.

- Social hierarchies: The nuances of social relationships may not be immediately apparent.

- Symbolic meanings: Objects or actions may carry symbolic weight that is not obvious to cultural outsiders.

Strategy: Pay close attention to how characters interact and react to each other. Look for explanations within the text or consult cultural guides for clarification.

Example: The significance of the kola nut in Chinua Achebe’s “Things Fall Apart” might be lost on readers unfamiliar with its cultural importance in Igbo society.

Emotional Disconnect

Readers may struggle to empathize with characters whose cultural experiences are vastly different from their own.

- Unfamiliar motivations: Characters’ decisions may seem irrational if the cultural context is not understood.

- Different value systems: What’s considered praiseworthy in one culture may be viewed negatively in another.

- Emotional expressions: The ways emotions are expressed and dealt with can vary significantly across cultures.

Strategy: Approach the text with an open mind and try to understand characters’ actions within their cultural context. Look for universal human experiences beneath cultural differences.

Example: Western readers might initially struggle to empathize with the protagonist’s choices in Khaled Hosseini’s “A Thousand Splendid Suns” without understanding the cultural constraints on women in Afghanistan.

Stereotyping and Overgeneralization

Readers may fall into the trap of stereotyping or overgeneralizing based on limited exposure to a culture.

- Confirmation bias: Readers might focus on aspects that confirm their preexisting notions about a culture.

- Exoticization: Unfamiliar cultural elements might be viewed as exotic or strange rather than normal within their context.

- Homogenization: Readers might assume that all members of a culture behave or think in the same way.

Strategy: Recognize that cultures are diverse and complex. Seek out multiple works from the same culture to gain a more nuanced understanding.

Example: Reading multiple works by different Native American authors can provide a more nuanced view than relying on a single text.

Narrative Structure and Pacing

Different cultures may have varying storytelling traditions that can be challenging for unfamiliar readers.

- Non-linear narratives: Some cultures favor non-linear storytelling, which can be confusing for readers used to chronological narratives.

- Pacing: The rhythm and pacing of storytelling can vary significantly across cultures.

- Emphasis on different elements: What’s considered important to include in a story can differ across cultures.

Strategy: Be patient with unfamiliar narrative structures. Try to appreciate the unique storytelling style rather than expecting it to conform to familiar patterns.

Example: The circular narrative structure in Gabriel García Márquez’s “One Hundred Years of Solitude” might be challenging for readers accustomed to linear plots.

Cultural References and Allusions

Texts may include references to historical events, folklore, or cultural figures that are unfamiliar to the reader.

- Historical allusions: References to historical events may be crucial for understanding the plot but not immediately recognizable.

- Literary and artistic references: Allusions to culturally specific works of art or literature may go unnoticed.

- Religious and mythological references: Symbols or stories from unfamiliar belief systems may be difficult to interpret.

Strategy: Use footnotes or endnotes if provided. Research unfamiliar references to deepen understanding. Consider reading companion guides or critical analyses alongside the text.

Example: Understanding references to the Mahabharata enhances the reading of Shashi Tharoor’s “The Great Indian Novel.”

Ethical and Moral Dilemmas

Readers may struggle with ethical or moral situations that are viewed differently in unfamiliar cultures.

- Cultural relativism: What’s considered ethical in one culture may be viewed as unethical in another.

- Conflicting values: Readers may find themselves at odds with the moral framework presented in the text.

- Historical context: Ethical norms of different historical periods may clash with contemporary values.

Strategy: Try to understand the ethical framework within its cultural and historical context. Reflect on why certain actions are considered right or wrongwithin the culture depicted.

Example: The practice of sati (widow burning) in some historical Indian contexts, as depicted in works like Amitav Ghosh’s “Sea of Poppies,” can be ethically challenging for modern readers.

Genre Expectations

Different cultures may have unique literary traditions and genre conventions that can be unfamiliar to readers.

- Unfamiliar genres: Some cultures have literary forms that don’t have direct equivalents in other traditions.

- Different conventions: Familiar genres may follow different rules or expectations in other cultures.